By Esther Mobley, May 19, 2016

I’m getting Judgment of Paris fatigue.

This Tuesday, May 24, marks the 40th anniversary of the competitive tasting in which Napa wines beat out their French counterparts. But it feels like the anniversary has lasted half a year — at least, I’ve been receiving press releases and promotional materials for that long. Has there ever been a wine milestone milked so relentlessly for PR pitches? It’s not just the victors of the competition who are commemorating the anniversary — and they are, with online-broadcasted parties at the wineries; days of festivities at the Smithsonian Institute; even a ticketed, $500/head commemorative dinner in Palm Springs. No, this season also saw the Judgment of Oakland, the Judgment of Paso, the Judgment of Charleston (S.C.), the Judgment of Geyserville. The syntax is wearily reminiscent of “the Uber of,” “the Netflix of” — and their ties equally tenuous.

“I call it the PDO — the Paris Tasting Decadal Oscillation,” laughs Bo Barrett. The CEO of the competition’s victorious Chateau Montelena riffs here on the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, a climate pattern that helps determine wine vintage conditions.

I won’t review what happened at the Paris Tasting here; for that, you can read the dozens (thousands?) of other articles about it published recently. And anyone truly interested in the history ought to read the excellent 2005 book “Judgment of Paris” by George Taber, the only journalist present at the 1976 event.

Unfortunately, most Americans have instead merely seen “Bottle Shock,” the 2008 film that makes Calistoga look like an Edenic playground for sexually alert young people with great hair. “Bottle Shock” gets so much of it wrong. Miljenko “Mike” Grgich, the winemaker who made Montelena’s winning Chardonnay, is completely omitted from the film. “I’m offended every day,” Grgich tells me. An original draft of the script, he says, portrayed him as “a complete lunatic,” and when they asked him to sign an approval, he asked instead simply to be written out.

Even the Barretts, who get all the film’s glory, take issue with several details. “Sure, we had used equipment, but we were never that broke,” Bo says. His parents Jim and Laura, portrayed as bitterly estranged, were in fact married in 1976. “And my mother never set foot in a country club in her life,” he adds. The cellar-adjacent boxing ring in which Jim and Bo work out their filial frustrations — quite the allegory — never existed. Nor did the Chardonnay ever turn brown. (Bo Barrett claims it turned pink; Grgich says it never changed colors.)

But ultimately I can forgive a commercial movie script for taking factual liberties. What bothers me more about the Paris Tasting hoopla is this: It reduces a long, complicated story to a simple myth. It makes it all seem as if the success and recognition of California wine were born in a single moment, thanks to just a couple of vintners.

Which is a vast oversimplification of California wine’s etiology. If you want a neat, easy story about how California wine was brought to global attention, let’s talk about the lifelong work of Robert Mondavi, who employed both of the winemakers whose wines took first place in Paris, Grgich and Warren Winiarski of Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars. If you want to talk about the late-20th century advances of Napa Valley winemaking in quality and technology, let’s look at Beaulieu Vineyards’ André Tchelistcheff, who mentored Grgich and had brought a group of Napa winemakers to France in conjunction with the Paris tasting.

But who can resist the themes of the Judgment of Paris, which has all the makings of a classic tale? It’s myth in the Barthesian sense of the word, a seamless promotion of the American dream, with the clarity of a Horatio Alger novel. It’s the victory of the meritocracy over the aristocracy. It’s an immigrant story: The winning winemakers were a Croatian immigrant and a Polish-American, both of whom arrived in Napa with almost nothing and proved themselves by dint of hard work. And it’s a story of capitalism: Grgich, having fled communist Yugoslavia for a land where property ownership was possible, had joined Montelena because he was granted partial ownership; the victory enabled him to found his own Grgich Hills.

“It was like the Copernican revolution,” asserts Winiarski, whose first career was as a classics professor. “A complete reversal of the way things were.”

It’s not that the results of the Paris Tasting weren’t a meaningful reflection of the quality that California wine had achieved by 1976. Certainly, the judges got it right: that California wines deserve a place at the table with the great wines of the world. “The goal was not to surpass French wines, but to speak about them in the same breath,” Winiarski says.

So why does the 40th carry so much more hype than previous anniversaries? Probably because it took 40 years for the tasting to seem this important. “The full implications of the tasting took a while to be expressable in a more truthful way,” says Winiarski. Four decades — a generation — have proven the outcome wasn’t a fluke. Compared with France, California wine is in its infancy; we still feel a thrill at affirmations of its greatness.

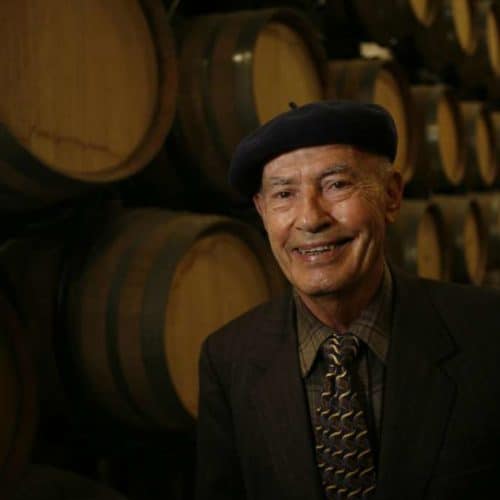

The other reason 40 feels so big, I suspect, is because the major players may not be around for the 50th. Grgich is 93; Winiarski, 87. This anniversary celebration doubles as celebrations of their entire lives in wine. To hear them recount their accomplishment now, in their twilight hours, is moving. “I’m still happy every day about it,” Grgich tells me at his winery, sporting a beret embroidered with Miljenko’s 90th Birthday. “That never disappeared.”

Each anniversary of the Paris Tasting is an opportunity to reexamine what’s truly important. In fact, the “Karate Kid” filmmaker (and vintner) Robert Mark Kamen is working on a film adaptation of Taber’s book, which will focus more on Winiarski and Stag’s Leap than on the Barretts and Montelena. Grgich, snubbed by “Bottle Shock,” has already filmed some scenes for the new film. (Kamen is still seeking investors.)

Perhaps the Paris Tasting’s greatest legacy is the precedent it set for emerging wine regions around the world. Not only an affirmation of Napa, it also helped shift the paradigm by which we judge wine quality. Today, we take for granted that wines from places like the Canary Islands, British Columbia and Slovenia, which have not traditionally been spoken of in the same breath as Bordeaux, are at least worth trying. We accept the possibility of their greatness.

For those emerging regions to fetch the prices, global demand and tourism that Napa Valley now enjoys, however, it may require a few more decades of marketing.